In 1850, John Stith Pemberton became a doctor at the ripe age of 19. He received his license to practice Thomsonian (or botanic) principles. This field was rooted in organic, herbal remedies and intended to cleanse the patient of toxins. It was not a very respected niche at the time and was treated with strong suspicion by the public.

Pemberton’s business opened its Atlanta doors in 1860 and had $35,000 worth of the latest most high-tech equipment on its side.

As the Civil War was beginning, he ultimately joined the army of the Confederacy in May 1862, and was made first lieutenant. As a founding member of the Third Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Pemberton defended the city of Columbus and was promoted to lieutenant colonel as a result - this is when his life would forever change.

In 1865, Lieutenant Colonel John Stith Pemberton of the Confederate Army was nearly fatally wounded with several gunshot wounds and a sword strike to the chest.

Seeking treatment, Pemberton was given morphine like many other wounded soldiers at the time. He easily became addicted.

After several years of dealing with his wounds and knowing he was an addict, he wanted a way to cure his morphine addiction.

Having this strong medical and scientific background, he returned home wounded, addicted, and fighting his own battles for years to come. Wanting to find a cure for his morphine addiction, Pemberton started tinkering in his lab and ultimately came across coca leaves as a way to help his addictive tendencies.

As Rick James would say, “cocaine is a hell of a drug.”

Introducing Pemberton’s French Wine Coca

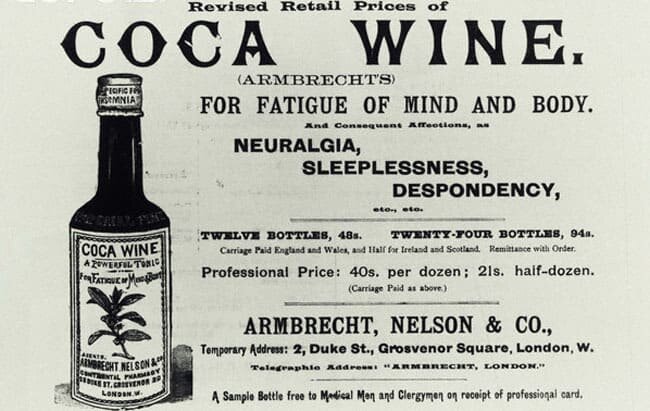

Nearly two decades after he suffered his wounds and experimenting on potential remedies, he created a medicinal tonic that became known as Pemberton’s French Wine Coca - which was based on similar alcoholic tonics he had heard of in France at the time.

This original beverage hit the market in 1885. It contained coca leaves that he had imported from South America that added a nice twist to the medicinal beverage. He sold the beverage as a “nerve tonic, mental aid, headache remedy, and a cure for morphine addiction.”

This first year he sold it in a local pharmacy in Atlanta, Georgia for five cents per drink. At this time, you couldn’t yet buy his concoctions as a 6 pack, it was solely handmade individually upon request. He made a grand total of $50 that first year, ultimately being in the negatives as he spent $70 on equipment and production.

Then in 1886 (one year later), Atlanta enacted the temperance legislation, meaning individuals at the time could not consume alcohol. So he was forced to restructure his beverage into a non-alcoholic version, which shifted his hard drink to a “soft drink”.

He began testing out versions of the syrup in a brass kettle in his backyard, finally finding a recipe that worked. He ultimately decided to drop the marketing as a medicinal tonic and now sell it as a fountain drink.

This new version was marketed as a “nerve and brain tonic” and was offered as a temperance alternative.

Frank Robinson, Pemberton’s bookkeeper, encouraged him to change the name this time around. Because he was using coca leaves and caffeine from kola nuts, Robinson suggested he change the name to...Coca-Cola.

It was also Robinson who designed the infamous logo and font of the brand that is still used today.

Source: https://medium.com/fgd1-the-archive/coca-cola-logo-1886-frank-mason-robinson-19d50f753027

This new concoction was starting to be sold in several other stores in the Atlanta area and was still only available upon individual request, not yet available in bottles or 6 packs. The buyer would request a Coca-Cola and the pharmacists would mix the syrup with carbonated water.

Despite having several investors, it still was not gaining the traction they had hoped. Then in 1887 (just another year after the new formula) Atlanta repealed its prohibition laws, so Pemberton switched his focus back to his original Wine Coca formula and once again, didn’t have much success.

So in 1888, he sold his remaining shares he had left for the business for a whopping $1,760.

Then in 1891 an Atlanta pharmacist, Asa Griggs Candler, purchased the rights to the business for $2,300 and in 1893 he officially trademarked the name Coca-Cola.

He brought Frank Robinson, the former bookkeeper, on board to focus on advertising and marketing.

Throughout the next several years they orchestrated the opening of bottle manufacturers and syrup-making plants in Dallas, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia. Finally, Coca-Cola was now available in 6 pack bottles.

Upon Candler’s leadership, sales rose from about 9,000 gallons of syrup in 1890 to 370,877 gallons in 1900, the turn of the century.

It was now being sold across America and even in Canada.

Then in 1903, as America was “cracking down” on drugs (see what I did there?), Candler decided to remove cocaine from its formula, although it still contained (and still does to this day) processed coca leaves.

Candler then began adding citric acid and a wide variety of fruit flavors, while still leaving the caffeine content from kola nuts, ultimately removing any medical claims the company once marketed.

Coca-Cola Becomes A Multi-Million Dollar Company

Around this time at the turn of the century, Coca-Cola had a net worth of around $100,000. Thanks to licensing agreements with independent bottle companies and beginning to be more widespread, 25 years later in 1919, Coca-Cola was now worth a lot more, and was sold to a group of investors for $25 million (1).

In 1916, a few years before it was sold, Coca-Cola decided to start selling their product in the iconic contoured bottle.

The leader of these investors was a businessman named Ernest Woodruff (that’s a very 1900s sounding name, isn’t it?). He and his son guided the company from 1923 - 1955, more than three decades.

The Rise In The ‘Diabesity’ Epidemic

During these years, a lot was changing in America, especially in terms of health and the health of Americans.

While Coca-Cola was being widely distributed, so were many of their competitors, like Pepsi, which we will talk more about in a bit. This was a huge reason for the increased sugar consumption over the years.

For a little historical context, in the 1920s sugar refineries were producing as much sugar in one single day (millions of pounds) as would have taken refineries in the 1820s an entire decade to manufacture.

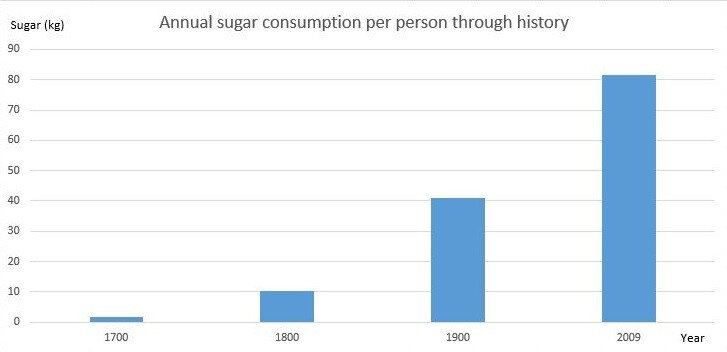

According to a research conducted by Natural Society, the average consumption of sugar from the year 1700 to 2009 rose substantially (2).

They went on to say:

The average person consumed approximately 4.9 grams each day (4 pounds of sugar each year) around 1700.

The average person consumed approximately 22.4 grams each day (18 pounds of sugar each year) around 1800.

The average person consumed approximately 112 grams each day, (90 pounds of sugar each year) around 1900.

50 percent of Americans consumed approximately 227 grams (1/2 pound) of sugar each day around 2009—equating to a 180 pounds each year.

The average person consumes 70 grams of fructose each day – 300 percent above the recommended amount.

I’d like to point out that the average amount of sugar consumption per person per year in 1900 (when Coca-Cola was making its wide expansion) was around 90 pounds.

Figure: Sugar consumption on average by approximate year

Think about that astronomical increase. At no point in our human history did humans have the sheer access to consume this amount of sugar even if they wanted to. So it seems as though we’ve lowered our standards in society - starting with the Dietary Guidelines.

According to the most recent Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2020-2025):

“Americans 2 years and older keep their intake of added sugars to less than 10% of their total daily calories. For example, in a 2,000 calorie diet, no more than 200 calories should come from added sugars (about 12 teaspoons)” (3, 4).

According to this recommendation by the Dietary Guidelines, they’re saying it is perfectly acceptable to create 10 percent of your body out of added sugars…

I don’t know about you, but why would you want to create 10% of your body’s tissues out of added sugars?

That is on top of the sugars you naturally get in food, too, by the way. The 10 percent added sugars recommendation is in addition to the 50 percent carbohydrate heavy diet they recommend and “natural sugars” contained in whole foods such as fruits and starchy vegetables.

For a little biochemical context, the average human bloodstream can only hold ~4 grams of glucose at any given time (roughly one teaspoon). Any excess will just get shuttled to your fat stores if you’re not active. And even if you are moderately active, the faulty recommendation that consuming 12 teaspoons of added sugars per day is still 12x the amount of sugar your bloodstream can handle.

Almost coincidentally, as investigative journalist, Gary Taubes, writes in his National Bestselling book, The Case Against Sugar, “in Copenhagen the number of diabetics treated in the city’s hospitals increased from ten in 1890 to 608 patients in 1924 - a near 60 fold increase. When the New York City health commissioner Haven Emerson and his colleague Louise Larimore published an analysis of diabetes mortality statistics in 1924, they reported a 400 percent increase in some American cities since 1900—almost 1,500 percent since the Civil War” (5).

While Coca-Cola was not the sole contributing factor to the diabesity epidemic, they are surely a large part to its birth. It was during these years (1945) of the Woodruff era that Coca-Cola officially trademarked the name “Coke”. And within this same timeframe, Time Magazine officially launched their May 1950 edition with Coke on their cover.

May 15th, 1950 Time Magazine Cover

Enter: High Fructose Corn Syrup

Fast forward a few decades as the American culture was shifting to a low-fat, eat less and exercise more paradigm, Coca-Cola was receiving a lot of challenge from its competitors - like Pepsi.

This was a time in our society when marketing was gaining huge traction. Grocery stores now contained virtually any food you could want with brands now marketing cartoon characters to target children and television commercials promoting their product, which has had massive implications on the current obesity and diabetes (diabesity) epidemic (6).

“Start em’ young and you will have them as a customer for life.”

Companies needed to find ways to keep a big bottom line, and clever marketing that touched the hearts of Americans was the way to do it.

In 1985, Coca-Cola was receiving much pushback from Pepsi. Pepsi decided to do what famously became known as the “Pepsi Challenge”. They had individuals blind taste test their product against Coke, and tell them which one they thought tasted better.

Enjoying This Content?

Join our weekly newsletter to receive exclusive content like the latest articles, episodes, recipes, and access to our Ultimate Autoimmune Reset™!

This worried Coke so much that they decided to reformulate their drink, creating a much sweeter tasting beverage.

Coke had not made a change this big since 1903 when they removed cocaine from their product.

While diet coke had already been out for a few years since 1982, they didn’t want to lose business to Pepsi. So they took their flagship product and made it a lot sweeter using high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) and labeled it as “New Coke”.

They launched this product in 1985. However, the public hated it.

It only took Coca-Cola 77 days before they brought back the original formula, only slightly altered to still contain high fructose corn syrup, just not taste as sweet.

This new campaign was called Coca Cola Classic.

The New Coke sold lightly for a few more years until 1992 when it was renamed Coke II, until it was ultimately removed altogether in 2002.

It was also in 1992-1993 that Coca-Cola began selling their product in recycled plastic.

When Coca-Cola made the switch to HFCS instead of regular sugar in 1985, it was purely a profit scheme on their part.

In the 1930s, President Roosevelt included farm subsidies in the New Deal, essentially to incentivize farmers to produce more corn in order to help from the Dust Bowl and Great Depression. Out of this mass production was born an absurd amount of corn that was sold cheap.

In the 1950s, high fructose corn syrup was invented and eventually caught hold in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. Companies realized that because corn was being mass produced in large quantities, high fructose corn syrup cold be bought and formulated into their product, making it much cheaper to manufacture and increase their profit margins.

So when Coca-Cola did this (along with the corn refiners association) it sparked more and more people to consume coke on a regular basis.

The Creation Of Vegetable Oils

Now this wasn’t the only health concern in the 1900s. The rise in vegetable oils was also a contributing factor to the health problems we started facing as Americans.

In the 1870s, the same time Pemberton was battling his own addictions and experimenting with his soon-to-be Coca-Cola drink in Atlanta, two brother-in-laws joined forces in Cincinnati to create a soap and candle manufacturing business.

William Procter and James Gamble set out on a quest to be the first company to make mass-produced individually wrapped bars of soap.

To be able to do this they needed to cut costs. While animal fats have been used as ancient fats for millenia for both nutrition consumption and soap, it was not a cheap source of fat in the 1800s, to say the least. Because home use of refrigerators wasn't common until the 1920s, buying and shipping animal products for mass quantity was very hard to do.

This meant they needed to find ways to replace it if they wanted to mass produce their products.

For their sole purpose of creating bars of soap, they ended up settling on palm, coconut, and cottonseed oil as their main sources, since they were able to be transported and handled at much cheaper costs than lard and tallow.

Needing a name for their new creation, Procter found refuge when he read a passage in the bible...

Psalm 45:8: "All thy garments smell of myrrh, and aloes, and cassia, out of the ivory palaces, whereby they have made thee glad." The word Ivory was trademarked, and in short order Americans all over the country would know the purity of this soap.

By 1905, P&G owned eight cottonseed mills in Mississippi. Cottonseed oil is a toxic byproduct of cotton production. Before it goes through over 20 steps of industrial processing, bleaching, and being deodorized, it is cloudy red and bitter to the taste because of a natural phytochemical called gossypol and is toxic to most animals, causing dangerous spikes in the body's potassium levels, organ damage, and paralysis.

Yet, it is a cheap byproduct that made their dreams of individually wrapped soap production possible.

Vegetable Oils For Human Consumption

Unfortunately at this time the electricity industry was really starting to replace the candle industry, so P&G looked for other ways to market their product and keep business alive.

In 1907, Edwin Kayser, a German chemist, wrote to P&G about a new chemical process that could create a solid fat from a liquid fat.

For decades, P&G researchers had been interested in producing a solid form of cottonseed oil, and Kayser described his new process as “the greatest possible importance to soap manufacturers” (7). The company purchased U.S. rights to the patents and created a lab on the Procter & Gamble campus, known as Ivorydale, to experiment with the new technology.

Soon the company's scientists produced a new creamy, pearly white substance out of cottonseed oil. It looked a lot like the most popular cooking fat used by humans for all human existence - lard.

Before long, P&G sold this new substance (known today as hydrogenated vegetable oil) to home cooks as a replacement for animal fats.

The new chemical process Kayser was referring to was obviously the process of hydrogenation. Hydrogenation simply means adding hydrogen atoms to the carbon chain length of a fatty acid, making it become more stable and more saturated with hydrogen atoms. The more saturated a fatty acid is, the more solid it is at room temperature.

The new product was initially named Krispo, but trademark complications forced P&G to look for another name. Their next try was Cryst, but was abandoned when someone in management noted a religious connotation. Eventually they chose the near-acronym Crisco, which can be derived from CRYStalized Cottonseed Oil.

In 1910, P&G filed a patent for the new creation describing it as “a food product consisting of vegetable oil, preferably cottonseed oil, partially hydrogenated, and hardened to a homogeneous white or yellowish semi-solid closely resembling lard. The special object of the invention is to provide a new food product for a shortening in cooking."

Thus, they introduced Crisco to the public in 1911, simultaneously the same time Americans were increasing their sugar consumption from soft drinks like Coca-Cola.

This was a time in our history when wives stayed home and cooked food for their working husbands. They used ancient cooking fats like butter and lard, which are shunned upon in today’s generation because of the events to come throughout the 1900s.

It was a real marketing challenge for P&G to convince stay-at-home housewives that Crisco was a better alternative than other popular cooking fats.

Health claims on food packaging were then unregulated, and the copywriters claimed that cottonseed oil was healthier than animal fats for digestion. Their first ad campaign introduced the all-vegetable shortening as “a healthier alternative to cooking with animal fats. . . and more economical than butter.” With one sentence, P&G had taken on its two closest competitors—lard and butter.

Never before had Procter & Gamble (or any company for that matter) put so much marketing support or advertising dollars behind a product. They hired the J. Walter Thompson Agency, America's first full service advertising agency staffed by real artists and professional writers.

Samples of Crisco were mailed to grocers, restaurants, nutritionists, and home economists. Eight alternative marketing strategies were tested in different cities and their impacts calculated and compared. Doughnuts were fried in Crisco and handed out in the streets. Women who purchased the new industrial fat got a free cookbook of Crisco recipes.

It opened with the line, "The culinary world is revising its entire cookbook on account of the advent of Crisco, a new and altogether different cooking fat." Recipes for asparagus soup, baked salmon with Colbert sauce, stuffed beets, curried cauliflower, and tomato sandwiches all called for three to four tablespoons of Crisco. It was similar to all other cookbooks at the time, but contained one major difference - all 615 recipes contained Crisco.

It was a beautiful marketing strategy that worked seemingly overnight. No more did humans have to use the expensive fats from animals to cook with. Rather, a newly-invented (cheaper!) shelf stable fat that looked the exact same began to replace nearly every cooking fat in the American kitchen.

It resulted in the sales of 2.6 million pounds of Crisco in 1912 and 60 million pounds just four years later. This new food bolstered the bottom line of a company whose other products were Ivory Soap, Lenox Soap, White Naptha Laundry Soap, and Star Soap. It also helped usher in the age of margarine as well as low-fat foods.

It seemed like the best invention at the time, until it wasn’t.

P&G sincerely didn’t know at the time how bad hydrogenated oils (trans fats) were. But over the years in the 1900s, heart disease, cancer, diabetes, learning problems, infertility, and other chronic diseases began to rise rapidly, as they still do. The science began to show just how harmful Crisco and trans fats truly were - but P&G couldn’t take a hit this big to their bottom line.

Scientists behind-the-scenes at P&G worked hard to cover it up. One scientist, Dr. Fred Mattson, can be credited with presenting the US government’s inconclusive Lipid Research Clinics Trials to the public as proof that animal fats cause heart disease (8). He was also one of the influencers (along with Ancel Keys) that persuaded the American Heart Association to preach the phony gospel of the Lipid Hypothesis.

This is the same hypothesis we learn about today - the same one I was taught in my college courses and that major media present as truth.

While we now come to widely accept the belief that trans fats are harmful to human health (this is one major reason P&G put their flagship product, Crisco up for sell on April 25th, 2001), we still cling to a faulty paradigm that says animal fats are bad, and vegetable oils are good.

Ironically, the same time the rise in soda and vegetable oil consumption rose in America, not so coincidentally did epidemic rates of chronic disease.

We have been told our entire lives that the optimal human diet emphasizes lean meats, fruits, vegetables, and grains - and that the healthiest fats come from polyunsaturated vegetable oils.

Most of these recommendations are based on the science that was done throughout these years as soda and vegetable oil consumption were on the rise. And as these companies did their part to hush the true science and promote the faulty science that supported their products, we saw millions of deaths as a result.

As these scientists responded to the skyrocketing numbers of heart disease cases, which had gone from a mere handful in 1900 to being the leading cause of death by 1950, they hypothesized that dietary fat, especially animal-based saturated fat was to blame.

Although it has never been proven that consumption of lard, tallow, and other animal-based products are the cause of heart disease and other chronic illness, we still have media headlines propping up how red meat attributes to cancer and heart disease, and unfortunately, misguided health professionals will tell you that saturated fat is absolutely to be avoided.

I mean, the idea that saturated fat is unhealthy has been so ingrained in our culture is seen more as “common sense” than it is based on scientific truth.

The more sugar and vegetable oils began to make their way into the kitchen of nearly every home in America throughout the 1900s, the more and more we saw skyrocketing rates of chronic disease. Researchers began asking why people were dying so rapidly all of a sudden. This, of course, lead to mass testing and studies being done.

Unfortunately, the studies that were done were observational-based studies and widely misinterpreted. To test a large part of the population (hundreds of thousands of people), epidemiology is the only real option. And what these studies do is ask participants to recall the food they’ve eaten in the past.

These types of studies can never prove causation. They can only show association and correlation.

However, these are the same studies that we now cling to when we tell Americans that long-consumed animal fats are bad for health.

By the 1950s, the belief that saturated fat was responsible for heart disease was beginning to make real traction thanks to a scientist named Ancel Keys. He is famously known for cherry picking his data that showed that the more people ate fat, the more they died from heart disease. However, when you include all the data from his findings, you’ll note that there is no correlation at all. Countries who ate more meat, died less. Whereas other countries who ate less meat, died more. And vice versa. There was no solid evidence on his part.

However, even though his faulty science was gaining traction, it was on September 23, 1955 when President Eisenhower suffered the first of several heart attacks. President Eisenhower’s personal doctor, Paul Dudley White, held a press conference and made it very clear for Americans, “stop smoking, reduce stress, and on the dietary front, cut down on saturated fat and cholesterol.”

Eisenhower himself became obsessed with his blood-cholesterol levels and religiously avoided foods with saturated fat. Instead he switched to polyunsaturated margarine and ate melba toast for breakfast - until he died of a heart attack in 1969 (he also smoked heavily, albeit he stopped smoking five years before he died).

And since this moment in history, the story about human nutrition has never been the same. It is not based on sound data, but rather deep pockets of Big Food and the connections they have with policy makers and politicians. We are at a place in our society where billion dollar companies like Coca-Cola and vegetable oil owners now control the market, and the minds of the consumers.

Taking ownership over your health

Nutrition used to be about pure survival, hunting your own food, foraging edible plants, and growing your own crops when in season - like it still is for any other species on this planet.

Now in the 21st century we are blessed to have access to these foods at a moment's notice, so we thankfully don’t have to face the cruel fate of food scarcity and starvation. But, unfortunately, that also comes at a cost of not knowing which foods in the grocery store aisle are healthy, and which ones are full of sugar and vegetable oils.

I can’t blame John Tith Pemberton or Procter & Gamble when they created their products. They did not know the disastrous effects they would have on the health of billions of humans just 100 years later. But who I do blame are the owners that now know this and aren’t choosing to do better.

The truth is we should do the best we can until we know better. And then when we know better, do better. Maya Angelou said this decades ago and her words still ring true today.

I know better - and I want to help those that don’t know better. Our environment is so incredibly stacked against us, so if your health isn’t where you want it to be, you don’t need to feel bad about it. It’s not your fault.

Billion dollar companies have such a strong hold over our society that it makes it near impossible to find a way out if you are not consciously looking for one. We have science funded by these corporations that skew the data every different direction, making it hard for even the best health professionals to know what is right, and what is wrong.

So if I had just one piece of advice for you, it would be this:

Vigorously seek to eliminate two things - vegetable oils and high fructose corn syrup. If you can eliminate these two foods from your diet, by default, you will eliminate nearly 90 percent of all foods in the grocery store.

If you can change your diet to the way humans had it before modern day chronic disease, you will have won. These companies only win when you give in to their product and buy them. You have the power to vote with your dollar. You have a choice who you invest in each and every day.

You can choose to invest in foods that promote health or you can invest in foods that promote disease.

It’s what you do right now that makes all the difference in the world. What are you going to do?